It’s an odd alliance at first glance. The Boston Preservation Alliance and Occupy JP have united to oppose demolishing the “Knight’s Children’s Center” on Huntington Ave. The Home for Little Wanderers is relocating to Walpole, and the latest plan for its site is to tear the buildings down and put up a high-end apartment building.

It’s an odd alliance at first glance. The Boston Preservation Alliance and Occupy JP have united to oppose demolishing the “Knight’s Children’s Center” on Huntington Ave. The Home for Little Wanderers is relocating to Walpole, and the latest plan for its site is to tear the buildings down and put up a high-end apartment building.

Here are the basics of the dispute from the Jamaica Plain Gazette:

Occupy JP calls for the space to be filled by owner-occupied triple-deckers, a homegrown remedy to poverty with a proven record,” the statement continued. “Spread the wealth or find the homeless, orphans, widows and others sleeping on your doorstep.”

Curtis Kemeny, whose Boston Residential Group is planning the high-end apartment building, previously told the Gazette that the existing buildings cannot be reused due to their age and the difficulty of reconfiguring them.

That includes a 1914 brick building at the core of the complex. Neiswander, a Jamaica Plain resident who said she was writing with the permission of the BPA’s board and executive director, noted that several other S. Huntington Avenue institutions have reused historic buildings. She noted that the 1914 building is “a sturdy brick building of human scale that should be eminently adapatable for residential use.”

It’s worth pointing out that the proponents of historic preservation and the proponents of affordable housing are not always natural allies. Often as not, for example, in the case of St. Aidan’s in Brookline, finally converted to affordable housing in 2010, housing advocates come up against preservationists and others who don’t want to see changes made.

Today, Tim Fernholz argues at GOOD that, “Local policies about land use and transit make America’s most productive places—our largest, wealthiest cities—prohibitively expensive for many people.”

The people already residing in those cities have enacted policies that have, in essence, built a wall around them. Limits on the size of buildings mean that fewer apartment units are built; demands that the needs of cars take precedence over the needs of people create vast parking lots that take up valuable land; zoning restrictions make it harder to create thriving neighborhoods with many types of housing and businesses. In his polemic, “The Rent Is Too Damn High,” Matt Yglesias notes while residents fight to preserve the character of iconic neighborhoods like Brooklyn’s Park Slope or Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown, those neighborhoods would be illegal to construct today.

Fernholz argues that high costs of living, combined with rising college debt, keep people from making the move to one of the country’s historically magnetic cities, like New York. Forget Georgetown. More dramatically, there’s the height restriction on all buildings in Washington DC, which gets a lot of blame for that city’s rising rents.

In the JP case (which, just to clarify, doesn’t involve affordable housing) the figurative keys to the bulldozers currently rest in the hands of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) after the Boston Landmarks Coalition (BLC) imposed a 90-day moratorium.

So, JP-ers, keep an eye on the alphabet soup and ponder this one awhile.

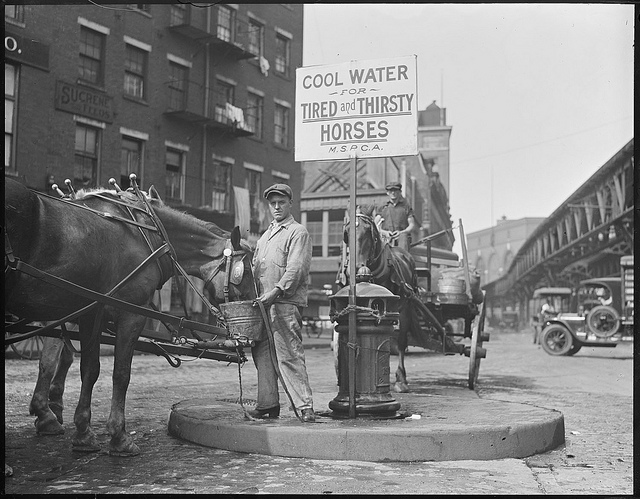

Photo of a downtown fountain for thirsty horses via

Photo of a downtown fountain for thirsty horses via

Tadeusz Kosciuszko:

Tadeusz Kosciuszko: